A QUICK COURSE IN BASIC

MOTORCYCLE JUMPING TERMINOLOGY

Johnny Airtime. Photo: Charles

Ellenberger

RAMPS AND MEASUREMENTS

You have had a hard time getting the

information you need in the past to properly report on motorcycle jumping.

Football is no problem, there are many who can prognosticate 'til the cows come

home in that sport. You can find plenty of people to give you an earful of

undisputed statistics on basketball, baseball, boxing or ping pong. In

motorcycle jumping, however, who are you going to believe - some sarsaparilla

selling huckster? If you want to know how far a jumper jumped, you can't find a

reliable record of it anywhere in the world. That will be changing now.

This media page will give you the lowdown on jumping: ramps and their shapes,

how jumps are measured, jumping styles, categories of

jumping records and what kind of bikes make the best

jumpers.

WHAT IS A RAMP?

A ramp is a structure with an angle designed to cause something to go up or

down. Ramps are found everywhere. Ramps

make many jobs easier, as the builders of the great pyramids would attest.

Wedges that hold doors open are ramps, and the design of a ramp is important for

each job. Volume controls on many forms of electronic equipment are often

represented in ramp shaped symbols. Even an ordinary screw is basically a ramp

wrapped around a pole. Let's face it - it's a ramp world!

In ramp to ramp jumping, you've got three important pieces of ramp structure:

1) Launch ramp, 2) Protective Apron, and 3) Landing ramp.

LAUNCH RAMP

The launch ramp is the first one the rider hits; it's the ramp that sends him

into the air. The shape of this ramp is critical. The rider must design his ramp

shape to be the best it can be for this particular application. He must build it

with good engineering and simple component parts.

The shape of the launch ramp is very important. A bad ramp shape can make you

or break you. The wedge ramps of yesteryear are going to become a thing of the

past.

Launch ramps can be many shapes, including wedge, bi-angle or two stage,

tri-angle or three stage, quadrangle or four stage, incremental ramps, true

radius ramps, decreasing radius elliptical transition and increasing radius

elliptical transition. There are even increasing to decreasing radius ramps, or

decreasing to increasing radius ramps. Each ramp has a different set of characteristics.

PROTECTIVE APRON

Any jumper jumping without a protective apron is considered a fool. A

protective apron is usually an approximately flat ramp section that is there to save a jumper's life if

he comes up short. The protective apron doesn't have to be flat, but it sits at

a flatter angle than the landing ramp itself. It is not included in the ramp gap measurement; it's

considered "invisible" and the rider must clear it to be successful,

especially on jumps where a specific ramp gap must be cleared.

Landing on a protective apron is no picnic. It's a flatter surface than the

landing ramp, so it's a

hard impact. Whatever pain a rider experiences when landing on a protective

apron is nothing compared to the pain he would have felt if the protective apron

was not there.

Sometimes the protective apron gets so huge it covers 1/2 the obstacle, which

takes away from the perception of danger. Some jumpers use a 50 foot long

protective apron for 120 foot jumps, which is considered going overboard. Other jumpers have 20', 16, 12', 10', 8',

4', and some have no protective apron.

For jumpers who use speedometers, a protective apron 20 feet long is

considered pretty good and 16 feet is too. 12 foot protective aprons are on the

short side, but anything shorter than that is getting really, really short,

which is not safe. This is for jumps in the 100 to 200' range.

For 200 to 300 foot jumps, a protective apron might be 30 or 40 feet long for

a rider with a speedometer, and 50 feet plus for those without.

Jumpers who don't use speedometers might need twice as much protective apron

for an equal amount of safety, so it takes away from the perceived danger.

Unfortunately, jumping ramp to ramp without a speedometer is not very

professional, and the tendency is to crash more than necessary from coming up

short and going long. Any professional jumper should be using a speedometer that

is designed for jumping.

Jumpers who jump ramp to ramp for any respectable distance without speedometers need an extra long landing ramp

and an extra long protective apron because they are not always very accurate in

distance.

LANDING RAMP

A landing ramp is the ramp the rider lands on. The shape of a landing ramp is not as important

as the shape of the launch ramp. It does, however, have to intercept the rider

from the trajectory imposed by the launch ramp. The angle of the landing ramp

has to be somewhere in the ballpark of

what really works. Some riders have set up landing ramps as steep as the launch

ramp, which is only good for short distances. The landing ramp will be about 10 degrees

flatter than the launch ramp on a decent ramp to ramp setup.

The rider should land in the sweet spot of the landing ramp. This is usually

about 5 feet to 20 feet down the landing ramp. Overjumping and landing 2/3 of

the way down the landing ramp makes for a really hard landing. When the rider

lands too far down the landing ramp, things can happen such as:

crashing from the sheer impact of the landing; the rider can loop out (the bike flips over

backwards with the front end too high) due to longer-than-expected hang time; the

rider can get the front end up too high, then land sitting down as a result, getting spinal

compression; the bike can suffer major damage; the impact can damage the ramp, and other problems.

Riders unable to accurately hit their mark are physically punished. Those who can

consistently hit their mark under varying conditions are rewarded.

HOW JUMPS ARE MEASURED

There are three measurements that are handy to have on typical jumps, and

that is, in order of importance, 1) Ramp gap, 2) Total jump distance, 3) Clear

gap.

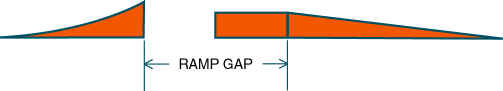

RAMP GAP

Everyone doing a jump wants to tell you their total jump distance. More

important and telling is the size of the ramp gap. The ramp gap is where the

obstacle goes. The obstacle should not extend beyond the ramp gap, under the

launch ramp or the landing ramp. The ramp gap is like the high bar in track

& field, where you have to clear the bar - it doesn't matter how much you

clear the bar, only that you cleared it. Stuffing cars, etc. under the landing

ramp or the launch ramp is considered cheating, and those cars outside of the

ramp gap will not be counted toward a record jump.

Every category of jumping has criteria.

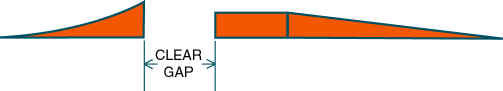

The ramp gap is the horizontal measurement from the high end of the launch

ramp to the beginning of the downside of the landing ramp. The protective apron

is considered "invisible" and is only there to save the rider's life

if he comes up short, as he surely will from time to time. If he comes up short,

he can land on the protective apron. If he lands on the protective apron, it's a

hard landing, but he can ride it out. It's possible that he will crash. Again,

it's there to save his life if he comes up short.

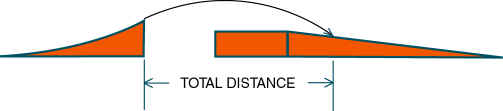

TOTAL JUMP DISTANCE

A jumper will most often tell you his total jump distance when asked how far

a jump was.

When a motorcycle lands on a landing ramp, it leaves a mark. That mark is

oval shaped. One end of the oval is farthest from the launch ramp. We don't care

about that end. We want to find the edge of the oval mark that is closest to the

launch ramp. The total jump distance is measured from the top of the landing ramp to the point on the oval shaped

tire mark closest to the launch ramp.

Some individuals watching a jump will mistakenly think a jumper is jumping

farther than he is. That is because the motorcycle has two wheels and some

jumpers have a difficult time keeping the front end down. Usually, when the rear wheel

hits the landing ramp, the rider has made the mark the jump will be measured

on. However, the front end is still in the air. It slaps down. That is where

untrained bystanders sometimes think the landing happened, which, at that speed, could be 25

feet farther down the ramp. Essentially, the jump is measured just like long

jumping in track & field; it's measured to the nearest mark.

CLEAR GAP

Spectators want to know how far the clear gap was. They sometimes mistake

ramp gap for clear gap. The clear gap is the gap between the launch ramp and the

protective apron; the gap where there's nothing to save the rider.

The clear gap can be quite small when a jumper doesn't use a speedometer and

has to construct a large protective apron. The jumps with the biggest clear gap

have an appeal all their own, even though the jumper isn't concerned with clear

gap; he's more concerned with ramp gap.

Jumpers eager to make their jumps look bigger want to remove protective apron

length.

Jumpers eager to live forever make a really large protective apron.

Jumpers who have to pay their own bills, transport their own ramps and don't

want to die quick build a protective apron somewhere between "long"

and "short".

CATEGORIES

OF JUMPING RECORDS

Click on the hyperlink below to look at a

vast array of ramp jumping record categories, but come back and read on!

World

Records

As you can see, records are in all different categories. You

can't group all jumps into one category, all-out distance. Each category

requires a distinct set of skills.

JUMPING STYLES

Each rider comes from a different

riding background.

Some were only street riders before they became jumpers. Street riders lack overall riding skill, not to

mention jumping skill. They are very one dimensional.

The next step up is flat trackers. Riders who

have flat track racing experience tend to jump on wedge or bi-angle ramps and

have a lack of style in the air; they usually

have a hard time keeping the front end down, lacking air sense and experience in

dragging the rear brake in mid-air. These riders were prevalent in the 1970s.

Desert Racers are highly capable

distance jumpers. They thrive at high speed across ragged terrain, so the high

speeds associated with ramp to ramp distance jumping are right up the alley of a

desert racer. These riders can adapt quickly and appropriately to unexpected

things coming at them at really high speed. They generally lack turning and

braking skill compared to a motocrosser, due to the ever-changing terrain over a

long desert race and a lack of repetition on any given obstacle.

Motocrossers

(supercrossers included) are the best qualified for ramp to ramp motorcycle jumping. They have the most

experience in the air and they're used to working in highly technical and

cramped environments on familiar and ever-changing courses, so they have lots of

repetitious experience doing things like floating through the air, pulling the

clutch and dragging the rear brake to keep the front end down before landing in

a rut berm on an off-camber hairpin turn. Motocrossers have deep experience and

can adapt to anything as conditions change. Motocrossers are the very best

jumpers of any motorcycle riding discipline. They have the most skill, the best

style, and they make the best ramp to ramp jumpers. If they are lacking in any

area, it's in a lack of experience riding at high speed. Motocrossers need to

get on a ramp to ramp motorcycle that is geared up and get accustomed to the

higher speeds of ramp to ramp distance jumping.

Freestylers are jumpers. They

exude incredible skills for throwing tricks in mid-air. The best freestylers

come from pro class motocross racing.

MOTORCYCLES

FOR RAMP TO RAMP JUMPING

Each rider, with his different style and

experience, will make a decision as to which bike would be the ultimate jumping

machine.

The best bike for jumping

has a combination of good features: